Whilst sipping a lovely Bladnoch over the festive break I was struck by just how much depth was cloaked in the spirit’s initially understated personality. This drew me to the much revisited topic of Whisky awards, and to considering which releases win them and ultimately, why? It seems quite difficult to find a Scotch that hasn’t attained gold before at least one set of “learned judges”, but more importantly, what of those awards that still hold merit amongst the sea of the somewhat dubious? The Malt Manic Awards, Cask Strength’s Best in Glass or Whisky Magazine’s annual awards are a few that maintain a level of trust, but just what is it that makes a winning malt?

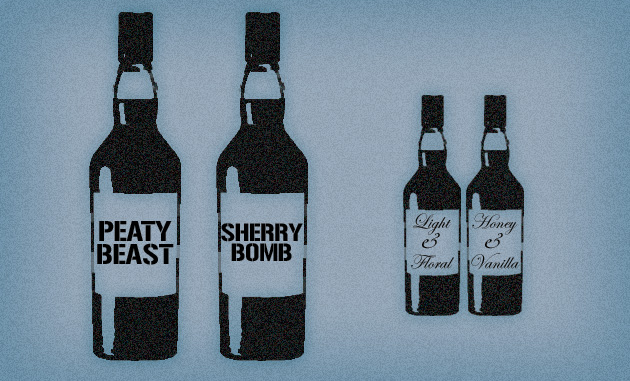

It seems to me that one theme runs deep as you look back over the bottles that have found themselves graced with top honours. Big whisky, powerful either by way of sherry, peat, active oak or a distinctly forceful character tends to steal the show. Indeed The Malt Maniacs are well known for their penchant for old, heavily sherried releases and last year’s awards did nothing to shake that view as another (admittedly lovely) Glendronach stood out above the rest. In the Best in Glass awards it was a forceful dram from Balcones and in The Whisky Magazine’s round up it was the similarly bold Yamazaki 25 year old. “Delicate whiskies find themselves lost in the crowd, outshone by the whisky equivalent of attention-hungry exhibitionists.”

Highlighting such a phenomenon is far from a criticism of the winners however, indeed they are all (in this case) of undoubtable quality and worthy of a place upon the pedestal in their own right. It is only the shadow this casts over the quieter, “whispering whiskies” – to quote Dave Broom – that concerns me, as for every peat-reeking Ardbeg or lush, intensely rich Glenfarclas whiskies there is graceful, comparatively fragile beauty standing to be overlooked.

It’s hardly surprising of course when you consider the mechanics of judging for such competitions; tasting large numbers of samples entirely, or partially, blind can cause the nuances of the delicate to find themselves lost in the crowd and outshone by the whisky equivalent of attention-hungry exhibitionists. Time is also an oft-overlooked factor, after all any whisky that must breathe well to unfold its richness and make a strong impact may be at a disadvantage as the number of samples to taste bears down upon a judge’s time, energy and palate. This strikes me not so much as a shame as an inevitability and one that, rather than consigning awards to a proverbial scrap-heap, is simply something to be aware of as you search feverishly for the latest medal-winning malt.

In truth, it’s not unusual to see a beautiful old whisky with layers of delicate complexity score in the 90s when tasted alone or in a small vertical, while failing to find favour with the majority of a panel during award scoring. If you have a glass of Bruichladdich XVII in front of you and if, as you drew in the quiet subtly of the Islay coast, delicate barley and whispers of ripe melon, you were wondering why there doesn’t seem to be a golden crest upon the label, the answer is simple. The profile you are enjoying is both it’s strength and weakness; it needs and rewards time, thought and patient appreciation the like of which you, dear reader, seem ideally poised to offer, while the rigours of the award process can prove less so.