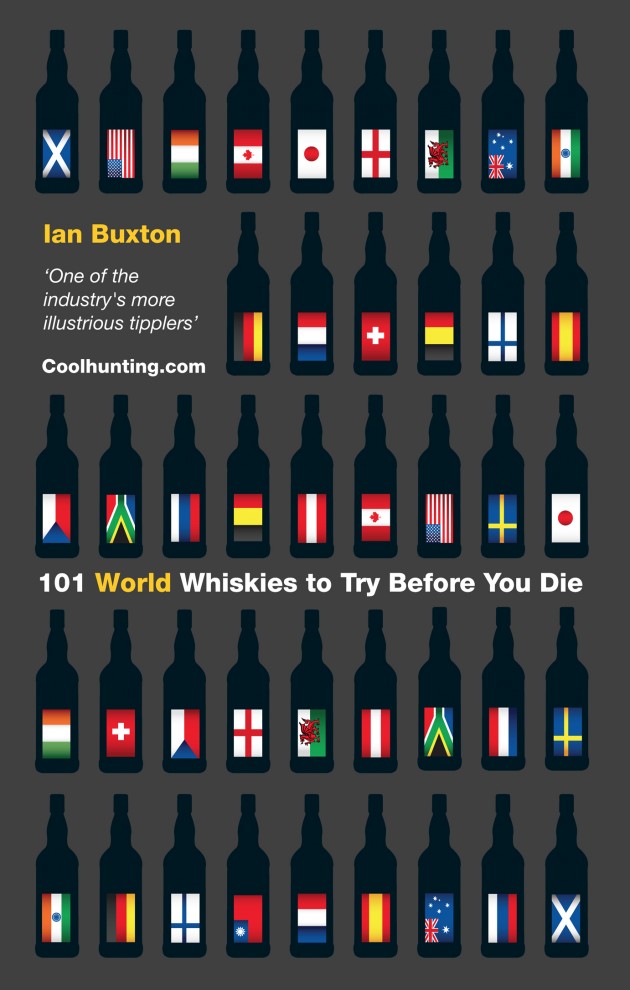

Ian Buxton is a name that many will already be familiar with, particularly for his recent books chronicling the definitive history of distilleries such as Glenfarclas and Glenglassaugh. Perhaps even more prominent in the minds of whisky fans though will be his 2010 release 101 Whiskies to Try Before You Die. The success of this excellent little book with its mix of dry wit, honesty and cutting irreverence was well deserved, and its follow up; 101 World Whiskies to Try Before You Die is reaching shelves now. With that in mind it felt like the perfect time to have a chat with Ian, ask a few questions that have been floating around in my mind for some time and get his views on whisky past and present.

1. Was there a particular event associated with whisky that took your early interest on to a great passion, and ultimately a chosen career path?

Sadly, no. Though I have worked in and around the drinks industry for more than 30 years, I actually drifted into whisky because I wanted to return to Scotland with my wife and then young family and I couldn’t find a job in the brewing industry here. I joined the blenders Robertson & Baxter and from there moved to Glenmorangie. I set up my own business in 1991 and things have evolved from there.

It would be entirely disingenuous to suggest there was ever a Damascene conversion or even a particularly focused career path. I certainly don’t feel I have had a career, more a fortunate life.

2. Were you surprised by the reaction to 101 Whiskies to Try Before You Die, and what do you feel made it such an instant favourite among whisky fans?

To be honest, both the publishers and I continue to be surprised by how well it has done. We expected it to be reasonably successful but we didn’t expect it to reprint six times; create its own Facebook club; inspire a dedicated but entirely independent website (www.somanywhiskies.com) and be picked up by a number of foreign publishers for translation (three currently, potentially nine if all the deals under negotiation come off). And because of that Hachette and I were naturally very keen for a follow-up.

Now that I’ve finished showing off, why did it do so well? Several factors played a part: a punchy, humorous title that appealed to a wide market; the convenient format; the striking and unusual cover design, which is deliberately different from the conventional look of a ‘whisky book’ and good marketing and sales work by Hachette. So that’s the formula if you want to copy it.

And I’d like to think the writing played a part. It was my contention that some (not all) whisky writing was getting rather pretentious and beginning to take itself rather too seriously. I wanted to put some of the fun back into whisky by taking a somewhat irreverent tone. While acknowledging great whisky I don’t feel we need to kowtow to it all the time.

3. The previous book placed considerable emphasis on Scotch whisky while its follow up obviously, as its name suggests, shines a light toward world whiskies, many of which will be largely new to a number of readers. To what extent did your research push you outside your own comfort zone and enlighten you to the wider whisk(e)y world, and does the sheer quality of these distillates surprise you?

I learned a huge amount working on this book – and was constantly reminded how much there is to learn. I met some really great people and tried some amazing whiskies, particularly various rye whiskies which hugely impressed me. But above all, I was struck by the pioneering and entrepreneurial approach of some small craft distillers. Sometimes I’ve listed a whisky more to support that spirit than for my view of the absolute quality of the whisky, though obviously I haven’t included anything that I didn’t think was more than drinkable.

4. You have spoken quite extensively in the past about your level of scepticism regarding the growing trend of speculating in whisky as an investment. With this in mind I wanted to ask your views on the recent Glenfarclas 1953 Wealth Solutions bottling. With your previous work alongside the distillery and your involvement in the presentation of this cask, was it somewhat bittersweet to see it marketed as an investment prospect?

This is my Jimmy Carr moment, isn’t it?

Obviously I was asked to write the accompanying book because I had written Glenfarclas’ official 175th anniversary book and I got involved after the cask had been selected (it’s superb, by the way). But I was initially quite reluctant and spent a long time discussing exactly the concerns you raise with George Grant, Ben Ellefsen at Master of Malt, who brokered the whole deal, and the people at Wealth Solutions in Poland. I came to respect and to like them because it became very clear that the project had arisen from their admiration for great Scotch whisky and from the fact that the two principals in the firm are actually serious collectors (not investors).

If you look at the promotional video (I think it’s still on YouTube and they have made a ‘Making of’ type video which I think will be uploaded soon) both George Grant and myself talk about the whisky as something to drink and enjoy, or as a collectible, not as an investment and that suggestion has crept in more to subsequent commentary than to the original marketing.

As a matter of record, the vast majority of bottles were sold in Poland at £2,500 which I thought more than reasonable for whisky of this age and quality. That was part of my decision. Very little was spent on lavish packaging and this price compares very well with anything else to be found in the market. I believe quite a number of the bottles have actually been drunk.

The fact that a few bottles have appeared on the secondary market at £6,000 I suppose shows what a great buy it was.

I remain of the view that whisky is not for investment, it is for drinking and enjoying. Both Master of Malt and Wealth Solutions know and respect my views and they seem to me an honest and straightforward group of people who made a very fair offer to their customers. I would happily work with them again if they came up with another whisky of this quality and an offer anything like as good.

5. In recent years you have produced detailed publications for distilleries like Glenfarclas, and Glenglassaugh. Given this and your time spent reading and re-issuing important, and long out of print, historical works under the “Classic Expressions” series, you must have learnt a great deal about the changing landscape through years of whisky production. What do you feel have been the most significant changes over the last 70-100 years?

How long have you got? In roughly chronological order one can think of the ‘What is Whisky?’ case of 1906 and subsequent Royal Commission that essentially laid the groundwork for today’s Scotch whisky industry; the consolidation of that industry under the influence of William Ross of the DCL in the 1920s; the boom of the 1950s and 60s, followed by the subsequent creation of the ‘whisky loch’ and severe depression in whisky production; further post-War consolidation, followed by today’s renaissance of independent distillers; the growth of single malt whisky from the 1970s and its acceleration and proliferation today and the renewed fashionability of all whisky, leading to a huge increase in production.

Would you believe that the advent of the steel shipping container in the late 1950s had a huge influence on whisky? Because of that, pilferage and breakage rates tumbled, insurance costs fell and the viability of exporting whisky round the world was transformed. No one talks about that yet it was actually a really big deal at the time.

When I entered the industry, somewhat by accident as I have mentioned, it was pretty moribund and many were forecasting its eventual demise in favour of vodka and white rums. It’s frankly incredible how it has bounced back and entered what seems to be a new golden age (though boom and bust have characterised past history, which is somewhat alarming).

Looking outside Scotland I should mention the growth of Japanese whisky from something of a joke in the 1950s and 1960s to its position commanding international respect today; rye whiskey has staged an amazing revival; craft distilling is huge in the USA and booming internationally in the most unexpected of places and even Irish whiskey, which was all but dead, is storming back to robust health. They’re making great whisky in Taiwan….

Behind all this there is a real depth of scientific understanding of how to make whisky and what contributes to really excellent quality. Lots of largely unsung work has been done to improve the whisky in your glass. And I think whisky is better marketed today.

Best of all there is a new generation of consumers coming through who are well-informed, enthusiastic, knowledgeable and able to pay for quality. This is just the best time to be involved in the whisky business and I’m privileged to play a tiny part in it.

6. There is a sense amongst many whisky lovers that (alongside other factors) greater use of quality American oak, and standardisation across much of the industry may have improved whisky generally, particularly at the cheaper end of the market, but at the expense of some individuality and character. What are your personal thoughts?

I really don’t see any seriously bad whisky being offered any more, which must be great news. As much due to the influence of good wood management as any other single factor the consistency of much everyday whisky has improved and the overall quality has risen.

Possibly because of this individual casks don’t stand out for exceptional quality as once they might have done but overall that’s good.

If you want individuality and character look no further than the small craft sector where that can be found in unprecedented abundance. And projects such as Buffalo Trace’s Single Oak range offer a lifetime of discovery.

I’m not overly concerned, though keeping up with it all is a constant challenge.

What may be a problem, if production continues to increase and all the projected new distilling capacity comes on stream, is maintaining the supply of good wood and finding somewhere to mature the whisky that the industry is talking of making.

7. If you had to pick one whisky featured in your new book to highlight here, which would it be and why?

I’m reluctant to do that. There is such an embarrassment of riches in the book, let alone in the whole world of whisky, that it would be invidious to settle on just one. And it would only be my opinion anyway and the whole point of the 101 Whiskies book is to encourage people to explore and discover for themselves. That’s why I don’t sit in judgement handing down scores from some largely specious position of self-awarded ‘expert’ authority. Make your own mind up!

8. Do you have any upcoming projects on the horizon for us to look forward to?

Yes, but right now I have to concentrate on promoting the new book. There are one or two irons in the fire though that I’m looking forward to getting into.

9. Lastly, give us three drams that stand out for you as unforgettable examples of the art of whisky making?

That’s just Q7 again, isn’t it? Sneaky.

OK, if you insist, and not in any particular order. Because it’s very clear in both books, I couldn’t deny that I really love Highland Park and they seldom seem to put a foot wrong.

- I thought Johnnie Walker Double Black was a pretty breath-taking achievement.

- I loved Hudson Manhattan Rye. And Templeton Rye. And Pikesville for that matter.

- The Taketsuru 21 Year Old is a desert island dram if ever I saw one.

- Glenfarclas 40 Year Old – at around £300, what’s not to like?

- Redbreast Cask Strength. Well, I nearly cried.

Oops, that’s more than three isn’t it? See the problem? Just buy the book for goodness’ sake!

Many thanks to Ian for his time, and for answering my questions in such depth. His new book is available through Amazon now, its a great read and a fitting follow up to the original.